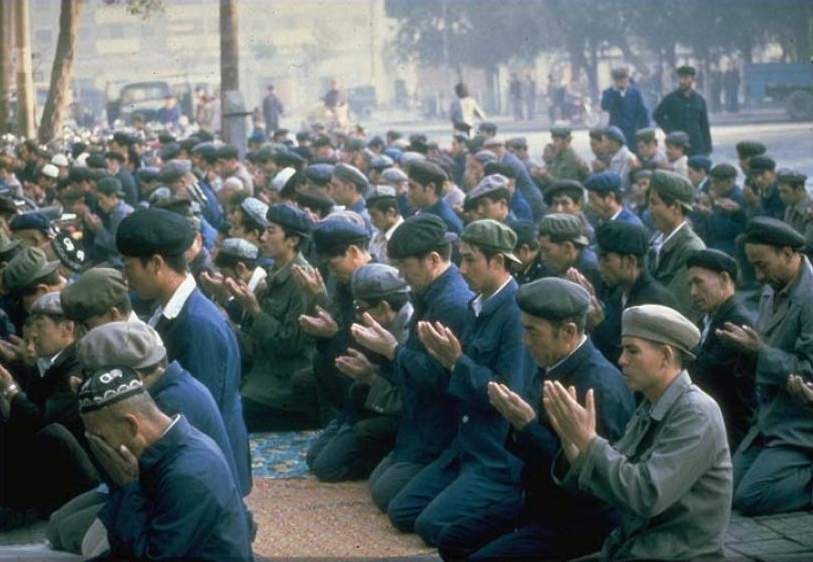

Xinjiang (which means 'new domain' in Chinese) is a huge, remote region in northwest China. It is home to a host of different peoples, including more than 15 million Muslims belonging to ethnic groups such as the Uygur, Kazak, Tajik, Uzbek, Kirgiz and Hui. It may surprise you to know that China, with approximately 25-30 million Muslims, has the ninth highest Islamic population of any country in the world, with about the same number as Iraq, Afghanistan and Saudi Arabia. These days few of Xinjiang's Muslims have ever heard the Gospel, and their spiritual condition is as barren as the huge Taklimakan Desert that dominates the region. There is not even one visible church among the Uygurs or any of the other Muslim groups. This has not always been the case, however. Few people are aware that a marvelous work of God occured in Xinjiang in the early decades of the 20th century, before it came to an abrupt and violent end in 1933. This is the little-known story of the Church in Xinjiang.

The vast desert expanses of northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region is much more historically, culturally, and linguistically akin to nearby Central Asian nations than to China.

The city of Yarkant (known as Shache in Chinese) has a population of around 700,000 people today, 95% of whom are Muslims. Located in Western Xinjiang, Yarkant has also been a hotbed of fanatical Islamists for centuries. The first Christian to experience the wrath of Yarkant's Muslims was Portuguese Catholic priest Benedict de Goës, who reached Yarkant in November 1603 after an exhausting 13 month trek from the Indian city of Agra. Goës was soon hauled before the local religious leaders, who tried to force him to denounce Christianity and embrace Islam. Goës gave a firm and clear rebuttal. The Yarkant leaders "could not understand how an intelligent man could profess any religion but their own. Elsewhere Goës was treated less civilly, several times barely escaping with his life from the swords of fanatics determined to make him invoke the name of Mohammed."

On one occasion Benedict de Goës was affronted by a furious Muslim who burst into the house where he was staying. The man placed "his sword against his breast, and threatened to plunge it in, if he did not instantly render homage to the prophet Mohammed. The courageous missionary calmly looked at him, gently put aside the sword, and said, 'Go, I know not who Mohammed is.'"

One of the greatest mission figures of the 19th century is a name few Christians in the English speaking world are familiar with. Nils Fredrick Höijer travelled through Russia, the Middle East, and Central Asia in the 1870s and 1880s, preaching the gospel in spite of tremendous opposition and difficulties. Through Höijer's tremendous courage and persistence the Swedish Missionary Society was founded in 1878. Dozens of pioneer missionaries were sent out over the following decades.

Nils Frederik Höijer - the great Swedish missionary pioneer.

Wherever the Swedes went they seemed to encounter great success. In 1892 they established a work at the strategic city of Kashgar in western Xinjiang. For the first two years the mission had just one worker - Mehmed Shukri, the son of a Muslim mullah (religious teacher) from Erzerum, Turkey. Shukri, who changed his name to Aveteranian after his conversion to Christ, proved to be a highly effective evangelist. In 1894 four Swedish missionaries joined him, and a mission base was established. Just one year later they started a satellite work at Yarkant, about 140 miles (227 km) southeast of Kashgar. From the very beginning the Swedish mission faced great opposition. Local Muslims "were infuriated that there was a Christian presence in their sacred territory, and they refused to allow the missionaries to rent any residence. For an extended period they had to live in a garden area, and even then several riots occurred. Finally, the Muslims, together with the Chinese authorities, incited a riot at Easter in 1899."

The Swedes overcame incessant opposition, and succeeded where no other Protestant mission had done before. Dozens of Muslims gave their lives to Jesus Christ. Trouble was never far away for the missionaries. One missionary and his converts were beaten and dragged through the streets of Yarkant. The Swedes remained at their post, and gradually won over many of the local people with their godly lives and sacrificial service. By 1926 more than 28,000 people had received treatment at the various Christian medical centres established throughout the region. The missionaries provided food during famines, clothed the poor, ran orphanages, and established ten schools. The Bible was translated into Uygur, and the missionaries printed and distributed copious amounts of Christian literature, boldly handing some of it to mullahs and other Islamic clerics. One report says that "During the years between 1919 and 1939 the adult communicant members of the Christian church of the country grew to number over 200, almost every one a convert from Islam; and if their children be included, the Christian community had about 500 members."

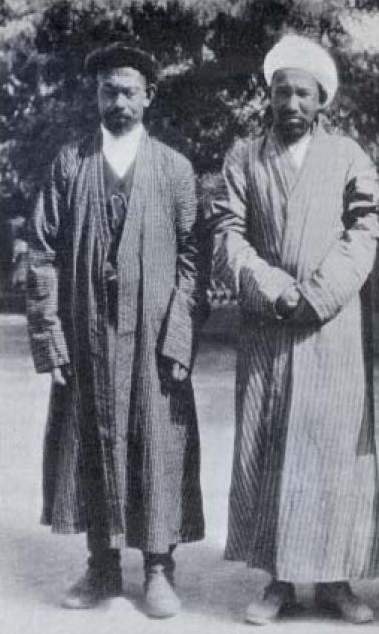

Christians outside the church at Kashgar in the early 1930s. All of the believers were converts from Islam, and most were slaughtered

by Muslims in 1933. There has been no visible church among the Muslims in Xinjiang to this day.

In April 1933 an armed Muslim faction from Khotan took control of Kashgar, Yarkant, and the other towns south of the Taklimakan Desert. Hundreds of Chinese were massacred in the assault, while their wives and daughters were captured and used as sex-slaves or forcibly married off to the deviant attackers, who gained control over most of Xinjiang and proclaimed the Turkish-Islamic Republic of Eastern Turkestan. One of their first objectives was to get rid of the Christians at Kashgar. Yarkant, and the other places the gospel had taken hold.

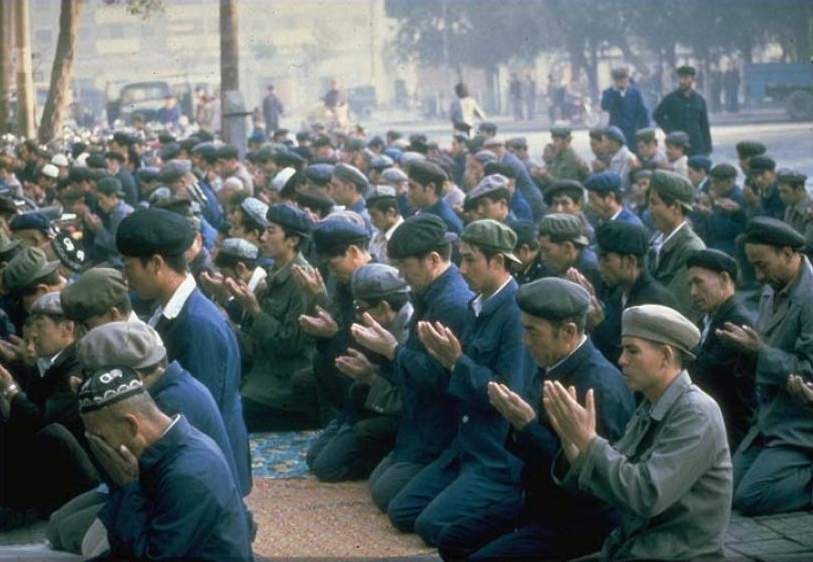

Chinese evangelists crossing the Taklimakan Desert in the 1940s

On April 27th the Khotan leader, Abdullah Khan, ordered the Swedish missionary Nyström to appear before him. Nyström was in charge of the mission's medical dispensary, which had helped thousands of people in Yarkant and surrounding districts. Nyström went to see Abdullah with his colleagues Arell and Hermansson. After being forced to wait a long time at the governor's mansion, "The Emir himself came into the room, holding a handkerchief to his nose (to filter the air contaminated by Christian breath). He began to ask such questions as 'You intended no doubt to use these poisons [medicine] to harm me and my followers?' Then he yelled, 'It is my duty, according to our law, to put you to death because by your preaching you have destroyed the faith of some of us! Out with you - Bind them.'"

After Nyström was bound, the cowardly Abdullah Khan personally struck the defenseless missionary. A group of soldiers armed with rifles, swords, and clubs, told the three missionaries to prepare for instant death. Abdullah Khan raised his sword and was about to start the slaughter when an aide sprang forward and begged for the missionaries' lives. They narrowly escaped, and were soon expelled from Xinjiang and returned to Sweden via Russia. Three other missionaries were allowed to remain in Xinjiang for a short time, before they were expelled across the Karakoram Pass into Pakistan.

After dealing with the missionaries, the cruel tyrant focused his energies on the local Christians, demonstrating a particular hatred toward all those who had converted from a Muslim background. The male Christians were beaten and thrown into prison at Yarkant and Kashgar. Some were beheaded, while others perished from the terrible tortures. The female Christians (including girls as young as 11) were forced to become wives of Muslim men. One of the girls later said, "We were called unbelievers, dogs, birds of ill omen, scum, swine, a shame to our people and accursed. They said, 'You must realize that this being done to save you from damnation. Now say that you will leave your rebellious ways and come back to the faith which was yours in the cradle and which you should never have left.'"

None of the Christian girls denounced their faith. At least 100 Christian men suffered martyrdom for their stand for Jesus Christ. Numbered among those who paid the ultimate price for their faith were:

Hassan Akhond, who was 20 years old. A Muslim who was later released from prison told how Hassan's soothing voice had often calmed the nerves of the prisoners at night as he sang hymns to Jesus. One night they heard him "faintly singing, 'Loved with Everlasting Love,' in Uygur. The next two nights [Hassan's] chain dragged, but after that was silence, and they concluded he had died of starvation."

Almost all of the Christians imprisoned at Kashgar died or were put to death. The martyrs included Khelil Akhond, Liu Losi the principal of the Chinese school, and many others. The Christians were herded into groups and then crammed into small, unventilated cells not large enough for each man to even sit down, "so that they all spent day and night on end on a half-standing, half-crouching position. The few who survived said they got aches and swelling in their knees and then in the upper part of the calves of the legs and in the thighs. Later mortification usually set in, and death followed. These unheated cells were bitterly cold, especially for prisoners who had not been allowed to take with them more clothes than those they stood up in when arrested. A number had been sent to prison only half clad. Some of them were put to unmentionable tortures. Consequently, apart from those who were executed, someone died almost every night, and sometimes four or five corpses were taken out of the cells in the morning. After several years' imprisonment, when all the leading Christians were dead, the half dozen survivors were admonished with threats and released."

The Church had suffered a horrific blow in Xinjiang. After the persecutions of the 1930s the few surviving ex-Muslim Christians faced the horrors of World War II, followed by more than half a century of Communist rule. To the present day there has never been such a wide-scale turning of Muslims to Christ in Xinjiang as there was when the Swedish Missionary Society was ministering there.

In the next issue we will look at the individual testimonies of several bold Xinjiang Christians who laid down their lives for Jesus in Xinjiang.

Note:

This article is included in Paul Hattaway's upcoming book, China's Christian Martyrs, which will contain more than 500 inspirational testimonies of those who died for Jesus Christ in China.

- www.asiaharvest.org/pages/newsletters/85-Aug2006-SheepAmongWolves-TheChurchinXinjiangPart1.pdf

----------------------

CHINA MARTYRS:

Sheep Among Wolves -

The Church in Xinjiang (Part Two)

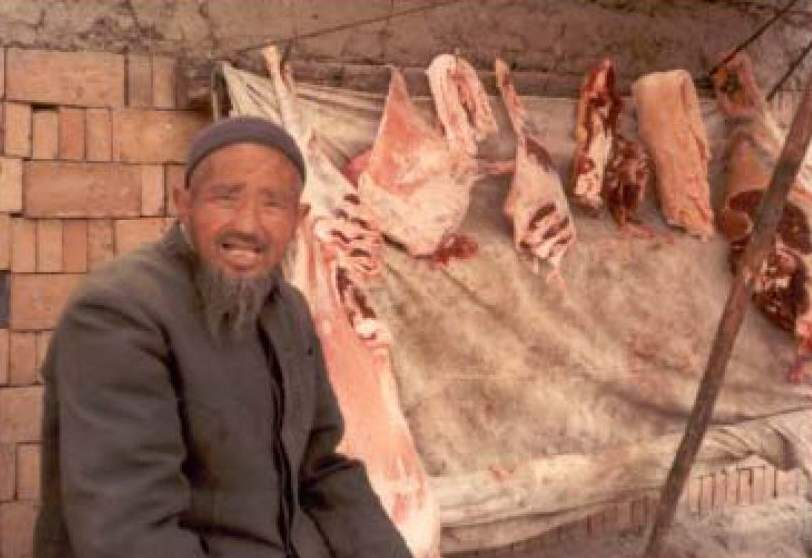

butcher shop

butcher shop

We continue our look at the history of the Church in Xinjiang, China's barren northwest region dominated by Muslims. In our last newsletter we examined how Swedish missionaries established the Gospel in Xinjiang in 1892, seeing a church emerge until brutal persecution in the 1930s brought the work to an end.

Ali Akhond

Ali Akhond grew up a dedicated Muslim. He faced Mecca and prayed at the five prescribed times each day, and was careful to obey the teaching of the Qu'ran. One day Ali rode his horse into the market at Kashgar, in China's northwest region of Xinjiang. While there he overheard an old man in a dusty gray cloak telling a group of students that he would never die. Ali thought the man, a Swedish missionary, was crazy, but he was strangely drawn to his claim that he would never die, and thought about it often.

Some time later Ali obtained work at Kashgar, leaving his wife back on the farm with his elderly father. Ali intended to use his time in the city to hear lectures on Islam, but instead he came into contact with the Swedish Mission. He often went to listen to their singing and preaching.

One night a missionary stood up and read the words of Jesus from the Bible, "I tell you the truth, if anyone keeps my word, he will never see death" (John 8:51). Ali remembered the time he had heard the old man say the same thing at the market, and he decided to find out what the Christians meant by this saying. He accepted some gospel literature and took it home to read, but a friend threw it into the fire, warning Ali that if he read it he would become an infidel. He returned to the mission and was given the same book, but this time another friend ripped it up before Ali had a chance to read it.

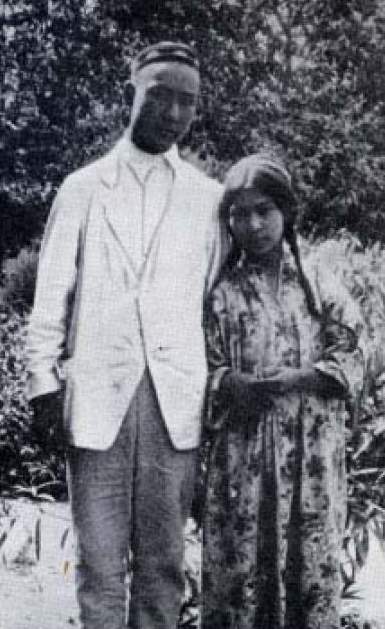

Ali Akhond (left) and a Christian at Kashgar

Undeterred, Ali Akhond secured yet more Christian literature and over the coming months closely observed the lives of the missionaries and their converts. What he saw impressed him. Whereas many marriages among Uygur people ended in divorce or discontent, the missionaries seemed to have genuine love and trust in their families. All of the Christians seemed to have an inner calm and joy that he longed for, and which Islam was unable to provide. A few years passed, and by this time Ali had taken a second wife. He struggled to support both wives in this polygamous arrangement. The missionaries later recalled how one day,

"it began to occur to Ali Akhond that the Swedes' successful married life, their unselfishness, truthfulness and honesty might be due to obeying the teaching of Christ; so he began to try to follow that teaching himself. About a year later he realized he now knew for certain that Christ was alive and that Christ was God. He saw the terrible thing that faced him. He would be cut off by his own people. But even so he decided that in common honesty he must throw in his lot with the despised Nazarene. He parted from his secondary wife, making provision for her and undertaking to support their little son who stayed with his mother. Then he asked to be prepared for baptism."

After his public baptism, everybody in Kashgar knew that Ali Akhond had turned his back on Islam and embraced the 'religion of the Crusaders'. Ali returned to his first wife, and after a few years she also repented and became a new creation in Christ. The transformation in Ali's life was startling, and he could not keep the message to himself. In the mid 1920s he was appointed as a full-time evangelist by the church in Kashgar, and he led many Muslims to faith in Jesus Christ. These advances came at great cost for the gifted preacher. He was constantly harrassed and threatened by his fellow countrymen, who considered him an infidel. According to one report, whenever Ali preached in a church service,

"there were always many more Muslims than Christians present, and when he preached on the story of the Prodigal Son, he could make everyone see the handsome young boy in a striped silk coat, white turban and crimson leather boots riding away from his father's house on a fine stallion. At Christmas there were often congregations of two or three hundred for the early morning service."

When the persecution started in 1933 there was nowhere to hide for the Christians, and certainly not for someone with such a high public profile as Ali Akhond. The missionaries were eventually expelled from Xinjiang, and most of the new believers were murdered. Ali Akhond was one of those who gained a martyr's crown at Kashgar. He had found God after seeking for him with all his heart, finally discovered the true meaning of what the missionaries had taught years before. He had kept the words of Jesus, and as a result never experienced spiritual death.

Habil and Hava

Habil and his sister Hava lived next door to a school run by the Swedish missionaries in Yarkant. Their father, Tokht Akhond, was a carpenter by trade. When Habil (Abel in English) was ten years old and Hava (Eva) was four, their mother suddenly died. This sad event threw the family into turmoil. The father went into huge debt to a Chinese opium smuggler.

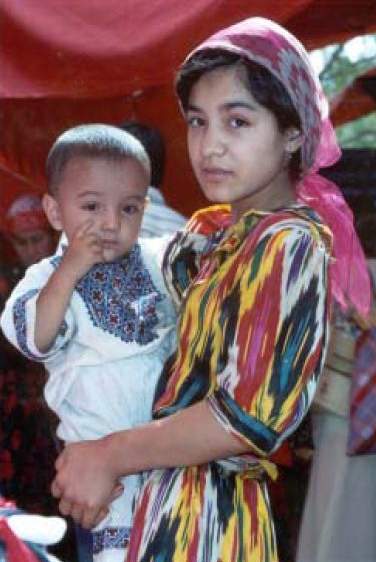

Habil and Hava at Yarkant in 1932

Two years later, in 1926, more heartache was added to the children when their father died. That same night the opium smuggler came to take Habil and his sister into slavery as payment for their father's debts. The children ran to the school and begged the missionaries to save them.

The Swedes did not have the kind of money owed to the creditor, but they devised a plan to protect and keep Habil and Hava. Habil had attended classes at the mission school for a number of years, but his father had not been able to pay the fees. The missionaries used this as a way to claim the children. They lodged a legal petition claiming the mission was owed a sum of money for unpaid fees. In return, they had accepted guardianship of Habil and his sister, and considered the debt paid in full. Because of his shady dealings, the opium smuggler did not dare contest the claim in court. The children were spared.

Gradually the grief-stricken children grew to love the Swedish missionaries. Habil enjoyed playing soccer, and proved better at the sport than other boys much older and larger than himself. He also enjoyed bird-watching. Little Hava came to love Gerda Andersson, who was in charge of the Girls' Home.

In 1931 a great evangelist named Yusuf Ryekhan came to live in Yarkant, and revival broke out among the Muslim population. Several of the young men connected to the mission put their faith in Christ and were baptized. Habil was one of them. In a Muslim society baptism is the point of no return for someone interested in Christianity. Habil knew it would cost him his friends, reputation and possibly his life, but he did not care. All he wanted to do was follow Jesus. The missionaries were greatly impressed by Habil's zeal and hunger for God, and at the end of 1932 he was invited to become the assistant principal of the mission school at Kashgar, even though he had only just turned 19.

Yarkant was overrun by the Khotan rebels on 11 April, 1933. Just before the road between Kashgar and Yarkant was cut off, Habil returned to Yarkant so he could take care of his sister. Hava was then 13, and many young girls and women were being raped and carried off by the rebels. The Swedish missionaries were rounded up and eventually expelled from Xinjiang, and the rebels turned their attention on those ex-Muslims who had deserted Islam.

Sensing the storm that was about to break, Habil drew a cross on a mud wall, and asked a Christian boy named Mehmen Niaz, "Do you see that?"

"Yes," the boy replied.

Then Habil drew a crown. "And do you see that? You see the cross comes first and then the crown."

That afternoon Habil and the other Christian boys prayed together, asking God to strengthen them for the ordeal ahead. Habil wept and prayed for courage to be faithful to his Saviour in life and death, like Stephen. Suddenly while they were singing a hymn, a shout went up to run. Soldiers surrounded the building and only one boy managed to escape. The Christians were roped together and taken to the governor's house, where Abdullah Khan had taken residence. Abdullah struck Habil over the head and yelled, "Shoot them all!" At the same time the wicked man signalled to a soldier that Habil should be separated from the others and untied.

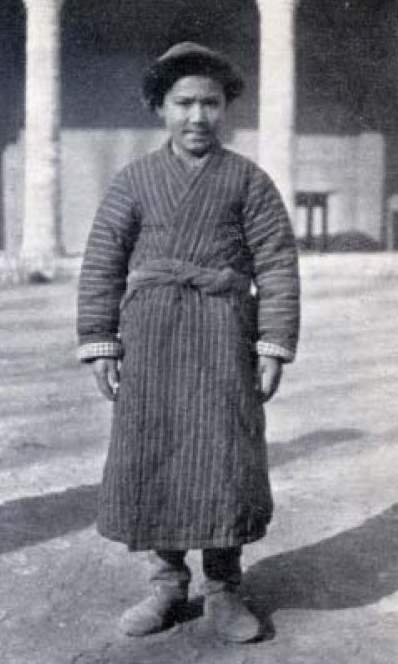

Habil knelt down and looked up to heaven with a peaceful look on his face. Then he looked across at his friends as if to bid them good-bye. The order was given, 'Fire!' Habil fell to the ground, and Abdullah shouted, "Finish him off with your sword."

The soldiers began to thrash the prisoners until two of the boys called out, "Shoot us, too, and put us out of our pain." When he had wreaked his anger on them, Abdullah had the Christians bound and sent to prison, and ordered thar Habil's body be thrown out for the dogs to eat. After it had remained untouched for three days, some Muslims buried it.

Habil at the age of 12

About a week later, Abdullah Khan ordered the 13 year old Hava to come to the governor's mansion. The believers prayed for her, afraid the wicked man planned to vent his lust on the pretty young girl's body. Just after sunrise the next morning Hava returned to the school and sank down on the floor. After wiping the tears from her eyes, she bravely recounted what had happened the previous night. The evil man locked the door and told Hava, "Now, you shall be mine!" Hava begged to be killed, so she could join her brother in heaven. Abdullah Khan was surprised to hear that the young girl was the sister of the man he had shot dead. Somehow this plea managed to touch even Abdullah's hard heart, and he allowed her to go free as long as he was provided another Christian girl in her place. That dreadful experience fell to a young lady named Buve Khan, who became Abdullah Khan's wife.

Hava and the other girls were forcibly married off to Muslim men. The man Hava was forced to wed suffered from syphilis, and she soon contracted the disease and also fell pregnant. The baby died at birth. Gerda Andersson was still in Yarkant at the time, and she heard what had happened to the beloved girl. The Swedish missionary sent a cart to Hava's house and collected her at the point of death, nursing her day and night until she recovered.

Having suffered the deaths of her mother, father, brother and newborn baby, young Hava's heart was crushed by the evil she had endured. Through the love and tears of the other Christians who survived, Hava continued to walk with the Lord, but several years later she died from the strain of the ordeal. She had not yet turned twenty.

- www.asiaharvest.org/pages/newsletters/86-Oct2006-SheepAmongWolves-TheChurchinXinjiangPart2.pdf